By Stacey Schamber

With a deficient response from, and sometimes the complete absence of, governments and the international community, civil society and women peacebuilders are taking the responsibility of responding to their communities needs. However, to ensure a strengthened response, they need the full collaboration with local governments.

The fifth weekly virtual meeting of the Women’s Alliance for Security Leadership (WASL) focused on women peacebuilders’ humanitarian response with guests including H.E. Ambassador Kåre Aas, Norwegian Ambassador to the US; Luc Duckendorf, from the Luxembourg Ministry of Foreign Affairs; ; Amjad Saleem from the International Federation of the Red Cross. The conversation focused on how women peacebuilders are at the forefront of this pandemic, despite a deficient response from governments and the international community, and their role in raising awareness about domestic violence and COVID-19.

As communities struggle to access water and primary healthcare, women are asking:

“Where is the State?”

The Absence of the State

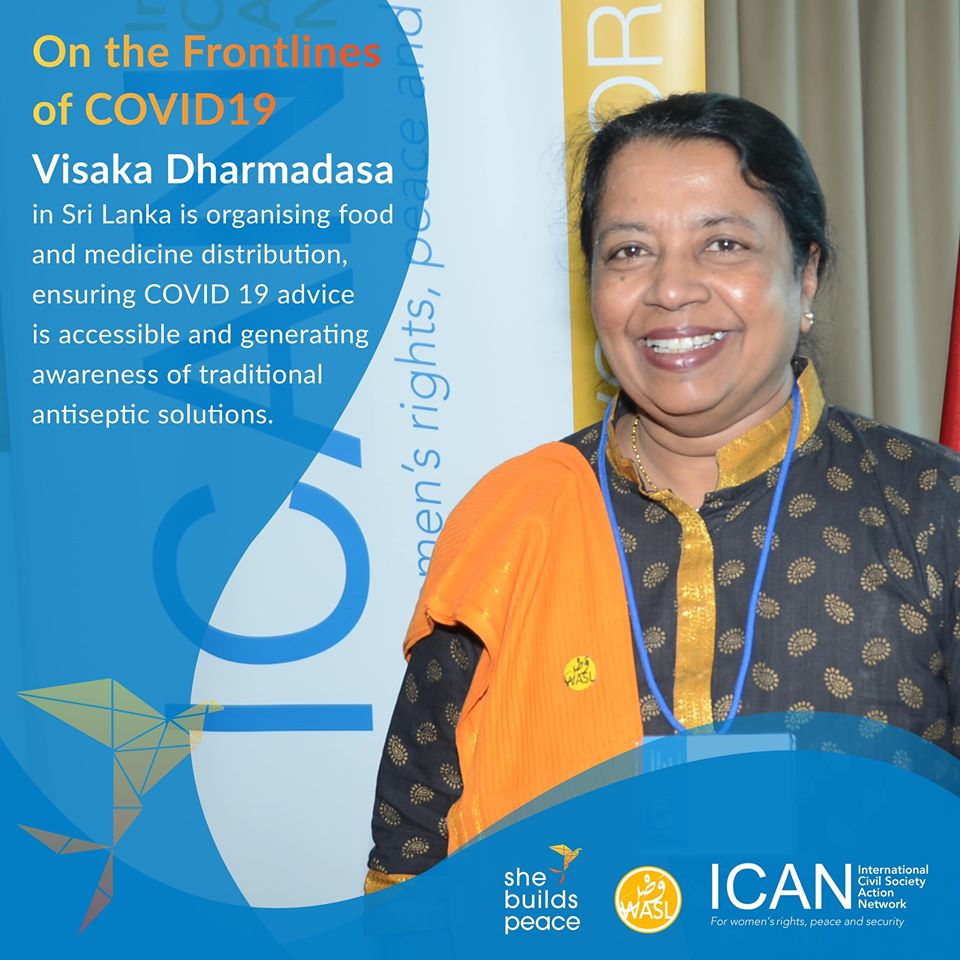

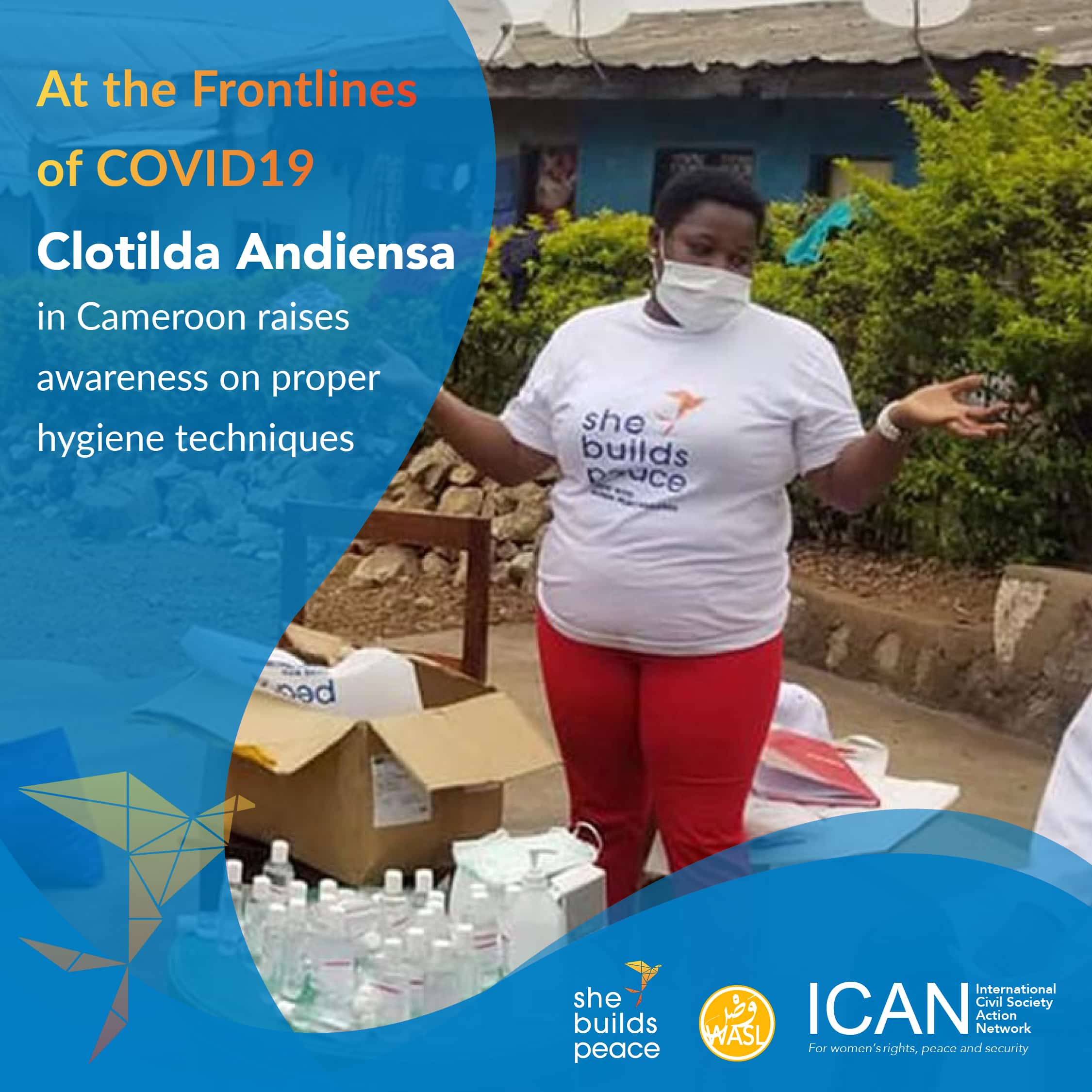

In Cameroon, the government and policies have no impact in remote areas, where communities struggle to access water and primary healthcare. Women are asking “should we just repair the water taps ourselves? Where is the state?” Displaced women and children in the north are forced to survive in small compounds, and face assault and sexual abuse and exploitation from military forces. Likewise, in Somalia, where people live communally, the virus has spread quickly, and the state has limited capacity. Even the significant humanitarian presence has not generated a robust response from the international community. In a small border community in Turkey, a local Syrian peacebuilder has been negotiating with the local government who has not yet supported her in meeting the needs of both Syrian and Turkish communities. In fact, authorities have relied on her for information, as her trusted community relationships enable her organization to deliver food to 1500 families. With weakened capacity, some states have resorted to a highly securitized response to COVID-19. For example, in Liberia, security forces beat a pregnant woman on her way to a hospital during the curfew time and another woman for not wearing a facemask. Women are appealing for inclusion in the national task force and for decentralization of markets to meet the economic needs of local communities.

With weakened capacity, some states have resorted to a highly securitized response to COVID-19.

Women peacebuilders, civil society, respond to domestic violence

It remains urgent and critical for governments to collaborate with civil society, including women peacebuilders, to ensure a strengthened response. Indonesia has emerged as one model where over 100 civil society representatives are working with local governments to integrate gender mainstreaming regulations across all sectors of their response. The government has established a hotline for psychosocial support, provided subsidies for women in microenterprises, and endorsed women’s leadership at the community level. The last version of the task force decree now includes the ministry of women’s empowerment and child protection. “With the new composition of the task force, the local government can engage the ministry of women’s empowerment and child protection at regional and local levels.” Women are now advocating to include domestic violence in the scope of the task force to mainstream gendered impacts of this crisis.

Many civil society organizations report an increase in domestic violence from lockdowns, evidenced by reports at hospitals and increased calls to hotlines. Women in Cameroon responded by including information about domestic violence into COVID-19 material, referring survivors to a one-stop center for services, and producing videos about the types of domestic violence, sharing a hotline number, as part of an advocacy campaign. Local radio stations will also broadcast segments about COVID-19 and domestic violence in the local language of Pidgin. In Kenya women also developed an online campaign about domestic violence and provided a hotline number and online counseling. A Syrian peacebuilder in Turkey is training three teams in psychosocial support and family violence to mitigate the impact of domestic violence.

Women Peacebuilders and a Gendered Response to COVID-19

Women peacebuilders understand and respond to the needs of their communities, often in simple and streamlined ways. For example, in Cameroon, women have included sanitary pads in the hygiene packages, distributed information to local clinics and translated it into Pidgin. They have partnered with local hospitals to reach out to pregnant women who avoid clinics and hospitals due to stigma and fears about the virus.

In Kenya they distribute personal protective equipment and conduct awareness raising to combat the social stigma, since families struggle with quarantine and stigma when a member has contracted the virus. One woman in Malaysia created an app for women to access validated healthcare information. In Pakistan women have sent activity packs to children and communicate with them through WhatsApp groups according to their school class. “Earlier when they had problems, they would come to the school and that would lessen their mental anxiety, but now they may be stuck with abusive elders or their mothers are victims of domestic violence.” Many of the activities also involve parents and grandparents to address concerns about domestic violence and the mental health impact on children.

Because of their trust and deep cultural understanding of their communities, women peacebuilders challenge myths about COVID-19 and disseminate accurate information in traditional societies. For example, in northern Cameroon, displaced women and their families have been chased away from communities because of fear of infection manifest in local beliefs in witchcraft. In Kenya some Muslims believe that they would not contract the virus because “God is with them,” and they seek treatment from Muslim clerics. In Somalia, religious leaders preached that dark-skinned people were not vulnerable to COVID-19; they have since ceased this message but have only recently started communicating health messages. Local civil society organizations conduct awareness raising campaigns to mitigate these myths. They also reach out to marginalized populations, which alleviates the existing tensions among social groups in conflict contexts. For example, in the Maldives, one organization provides food to people from Bangladesh who reside without legal status or work. Some have contracted COVID-19 leading to the perception that they have spread the virus. A Syrian peacebuilder in Turkey, by providing food to the local Turkish community, builds social cohesion in a country stressed from hosting Syrian refugees.

Civil society is there ready to take the lead, but by what means and by which roads.

Across the world, women and local civil society mobilize to address the impact of domestic violence and COVID-19, but they need the resources, recognition, and support of their governments and the international community. In the words of a peacebuilder from Cameroon, “civil society is there ready to take the lead, but by what means and by which roads.” Organizations like the IFRC can advocate with governments for close collaboration with civil society to amplify a strong, conflict sensitive, gender responsive strategy to COVID-19.

Click here to download the call summary in PDF format

Summaries of the rest of the calls can be accessed here

The WASL calls are held weekly on Thursdays at 9am EDT.

For more information please contact Melinda Holmes, WASL Program Director